All art and illustrations in this series and article have been contributed kindly by the lovely Linran, who can be found at https://linranjiang.info/

In order to begin the process of making katsuobushi, skipjack tuna or katsuo (Katsuwonus pelamis) is first flash-frozen on the fishing boats which catch it, down to -30 to -50 ° C. Once at the factory, the heads and internal organs are removed. The katsuo are cleaned with water, and then filleted into three pieces in the same way you would fillet a fish in a French kitchen.

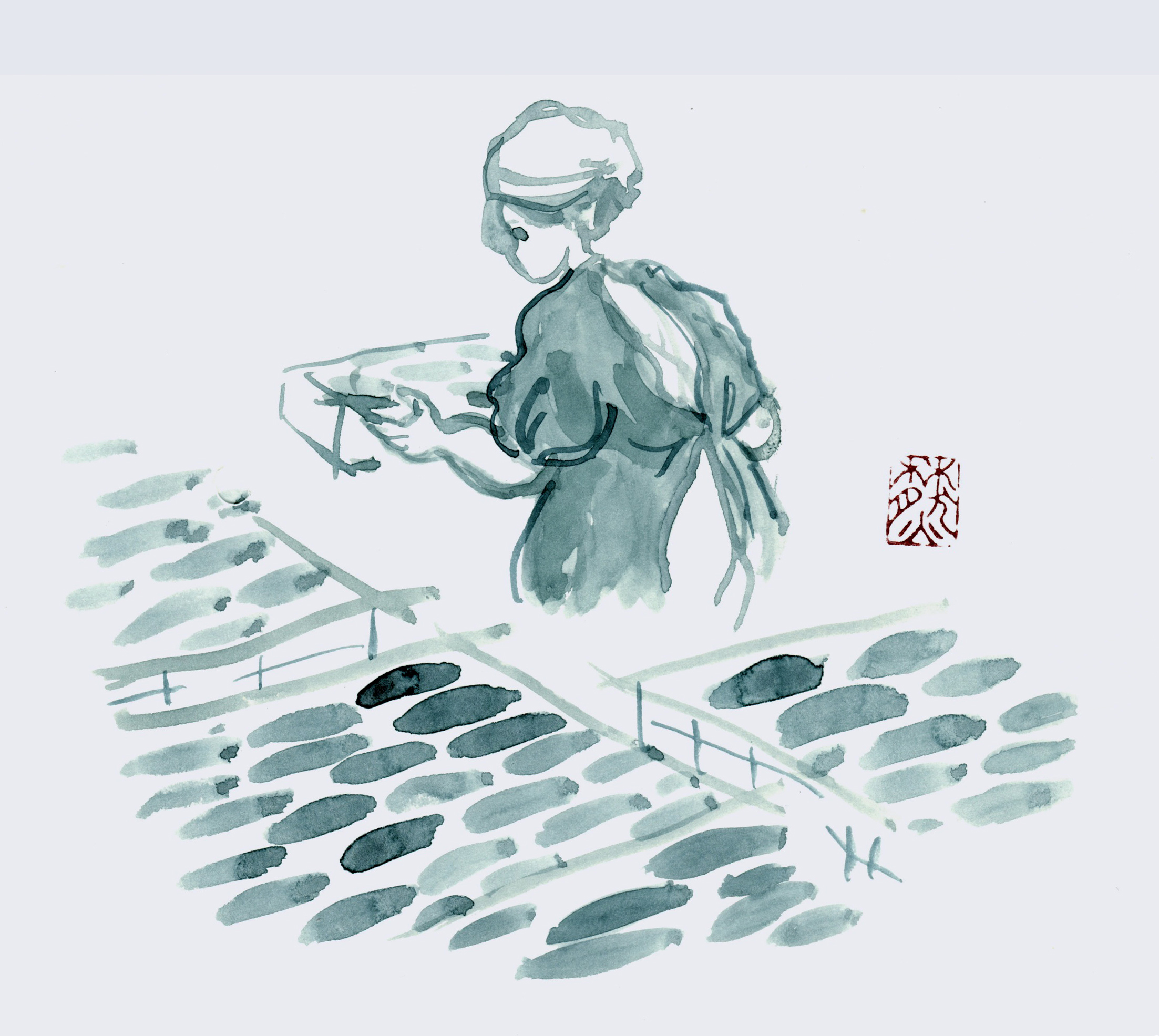

The filleted Katsuo are arranged neatly on a metal basket, which is then lowered into simmering water. The fillets need to be arranged in straight lines. If they aren’t, the cooked fillets will be misshapen, and very difficult to shave once dried.

The fillets are simmered – vigorous boiling would damage them – in hot water at 75 to 98°C for 60 to 90 minutes. The skin is left on during the cooking process to prevent shrinking which would also deform the fillets.

Once cooked, the fillets are placed in a water tank and the skin, scales and excess fat are washed off. The fillets are then lifted out of the water by hand and deboned one by one. The process is done by hand to minimise damage to the fillets. Any bones left behind would also destroy the final shape of the fillet once it dried due to shrinkage.

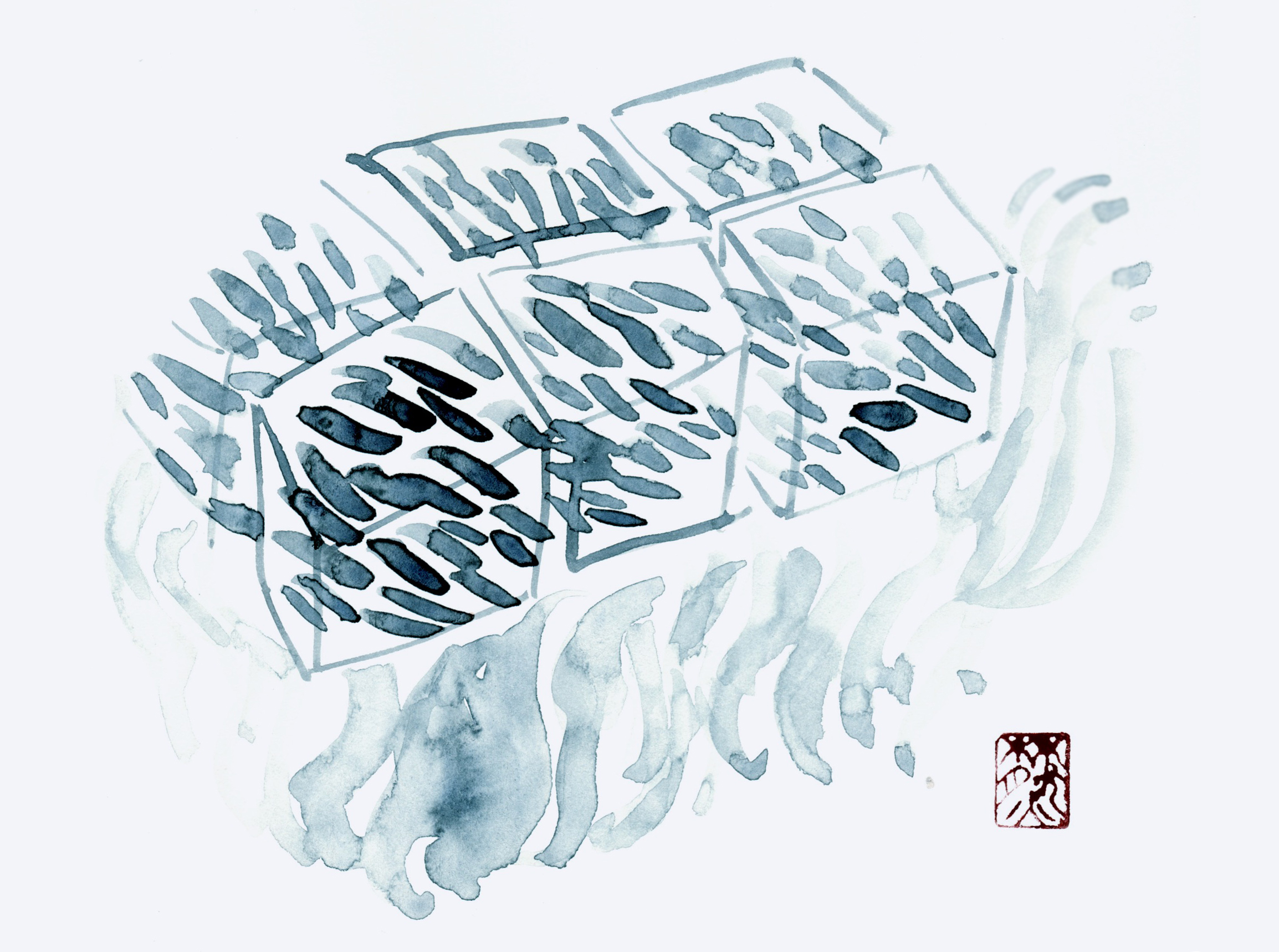

They are then placed in a wood burning smoker, fuelled by various woods such as oak and cherry. The different woods impact different, complex flavours. The first smoking that is carried out is called the “first fire” ( 一番火 ichiban hi) or “water drainage fire” (水抜き焙乾 mizunuki baikan) as it evaporates the majority of the water from inside the fillets.

Once smoked, the fillets are left to cool before being repaired. As not all the fillets are in perfect shape after smoking and deboning, any holes or damage on them are repaired using a paste. The paste is made from two parts boiled meat and one part raw meat, and is used to fill out the fillets, just like clay or plaster. They are then lined up again and undergo the second smoking or “second fire” (二番火 niban hi).

This smoking and cooling is repeated ten to fifteen times, with each cooling period allowing moisture from the inside core of the fish to reach the surface, further drying out the fillets. If the fillets were dried in one go, the surface of the fillets would harden and the inside of the fish would still contain water. At this stage each fillet contains around 28% in water. The fillets are also covered with “tar” or a thick layer of smoke particulates, which prevents the fat and flesh of the fish from oxidising. This preserves the flavour of the fillets.

These fillets are known as demon bushi (鬼節 onibushi) due to their black charred appearance. At this point the fillets can be packaged and sold as onibushi or leftover bushi (荒節 arabushi).

After the smoking process, the fillets are sun-dried for about half a day. The fillets are then scraped by hand to remove the tar, and any fat which has formed on the surface. If they are sun dried for any longer, the remaining internal moisture in the fillet would reach the surface, resulting in unwanted mold growth. The resulting scraped fillets are known as naked bushi (裸節 hadaka bushi, and the scraped off sections of the fillets are known as red peelings (赤むき aka muki).

The fillets are then left to dry for another 2 or 3 days before being inoculated with patented katsuobushi molds (鰹節カビ katsuobushi kabi) called Aspergillus glaucus and Eurotium herbariorum. Then, they are stored in a room called a muro (ムロ庫 muroko) with controlled temperature and humidity designed for optimal growth. The Aspergillus glaucus grows it roots (hyphae) into the fish and exacts out even more moisture, fully covering the fillet in two to three days. The fillets are then dried in the sun and brushed gently with a brush. This process of inoculation, growing and drying is repeated 3 to 6 times. At this point, the Katsuobushi is extremely fragile and any rain water that might drip on the fillets during the sun-drying process will result in a permanent mark on the fillet.

Aspergillus glaucus is in the same family as Aspergillus oryzae (koji) which is used when making sake. The main difference is that Aspergillus glaucus more readily breaks down amino acids, and thus ferments protein much better than Aspergillus oryzae which is better at breaking down starches.

The entire process takes up to four months, and about 83% of the fish’s weight in water will be lost. The remaining fillets will contain around 12 to 15% in water, and a clear crisp sound can be heard when two fillets are hit together.

The audio recording of two pieces of katsuobushi being tapped together is linked below – please be careful if wearing earphones.

In summary:

- The katsuo are gutted and filleted

- The fillets are simmered to firm up the flesh

- They are deboned by hand

- Fillets are smoked for four to six hours a day, for up to a month

- Remaining water in the fillets is evaporated through cooling them down between smoking sessions.

- At this stage, fillets can be sold as leftover bushi (荒節 arabushi).

- Tar and fats which have formed on the fillets is then scraped off

- The fillets are inoculated with Aspergillus glaucus and Eurotium herbariorum

- Aspergillus glaucus is allowed to cultivate for up to 2 weeks under controlled conditions

- Aspergillus glaucus is scraped off, and the fillets are allowed to dry in the sun. The process is repeated again

- Fillets at this stage can be sold as high-grade inoculated katsuobushi, called karebushi (枯節)

- The inoculation and sun drying process is then repeated at least three more times.

- These fillets can then be sold as “true” karebushi (本枯節 hon karebushi)

The extensive drying and smoking, combined with the moisture extracted by Aspergillus glaucus, the finished Katsuobushi is as dry as a piece of wood, and reveals a gorgeous deep ruby color when shaved.

Different Production Methods for Katsuobushi Around Japan

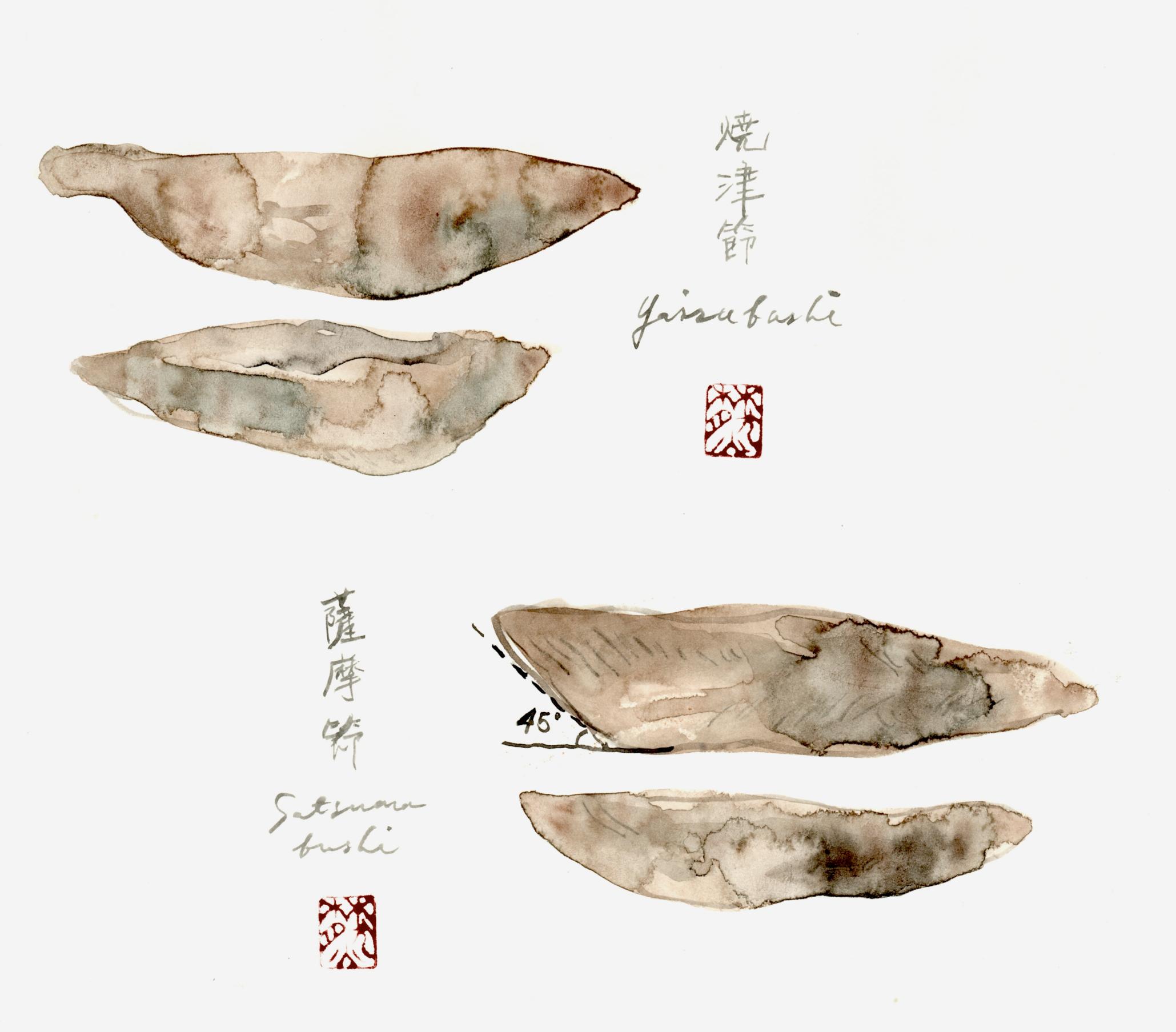

The majority of katsuobushi produced and supplied in Japan is Yaizu bushi (焼津節), this means that any unlabeled katsuobushi is usually going to be Yaizu bushi. Yaizu bushi is also known as improved true bushi (改良型本節 kairyougata honbushi). Yaizu bushi can be identified by its narrowing at the neck, which was said to aid in hanging it up with a rope during storage. When initially cut with a filleting knife, the spine of the fish is only easier to cut through when cut closer to the head of the fish.

Satsuma bushi (薩摩節), is another type of katsuobushi, very rarely found in Japan. It is made in Kagoshima (鹿児島). Whilst Yaizu bushi is placed in a tank of water to be skinned and deboned by hand (water de-boning, 水骨), Satsuma bushi is filleted (生切り nama kiri), then skinned and deboned (land de-boning 陸骨) whilst the fish is still raw. Anybody who has tried to do this with cooked fish or raw fish knows how much harder it is to do with raw fish. It also requires the fish to be as fresh as possible so that it is firm enough for the pin bones to be removed. This means that only very skilled craftsmen are able to make Satsuma bushi.

Compared to Yaizu bushi, Satsuma bushi is made by cutting off the head at a 45 degree angle, making it wider compared to Yaizu bushi. This also means that Yaizu bushi has a higher yield.

*Some premium katsuo meant for high end Katsuobushi are not frozen but brought back fresh in order to maintain their quality. This is more costly as the boat has to stay at sea for a much shorter period of time and cannot catch as much fish. The typical Katsuo size caught is 4.5 to 6kg.

This article leads on to Different Parts and Types of Katsuobushi (鰹節の解剖学).

I’m loving your site! Stumbled across while looking for information on how to store katsuobushi that I got in Japan. I’m still a little unsure how to keep it for years…do I wrap and vacuum seal each time after I shave some? Do I scrape off the mold? So many questions! But I love all the information you are sharing. Thank you!